Bringing a Spring Drive watch to life.

Even in our technologically advanced age, the creation of a fine timepiece takes much more than engineering; it requires the skills and ingenuity of watchmakers whose ability to assemble and adjust two hundred or more components by hand is just as important as the manufacturing of each part to a precision of 10 micron. It might be hard to believe but, even if a component in a Grand Seiko Spring Drive watch is made to such astonishingly high tolerances (and a micron is 1,000th of a millimeter), it still requires human ingenuity, patience and talent to assemble all two hundred or more components in a way that ensures the perfection of the movement. So who are the watchmakers who take on this task and what drives them? Let’s meet some of the remarkable people at the Shinshu Watch Studio and how Grand Seiko came to develop their expertise.

In Japan, there has always been great interest in skills and precision competitions. After dominating the Japanese Observatory competitions for watch precision for several years, Daini Seikosha and Suwa Seikosha began participating in the Neuchâtel Observatory Concours in Switzerland in 1963. Just four years later in 1967, their mechanical watches captured second and third places in the corporate group awards and at the 1968 Geneva Observatory Concours, Suwa Seikosha won first place for mechanical watches. Suwa Seikosha also won the gold medal in the watch category of the World Skills Competition for five consecutive years beginning in 1977. Today, neither these watch “concours” nor the international skills competitions exist in the same way but the Japanese National Skills Competition has been revived, in which young people from various fields compete for recognition as the best in Japan in their respective skills. Watchmaking is, once again, one of the skills included in this event.

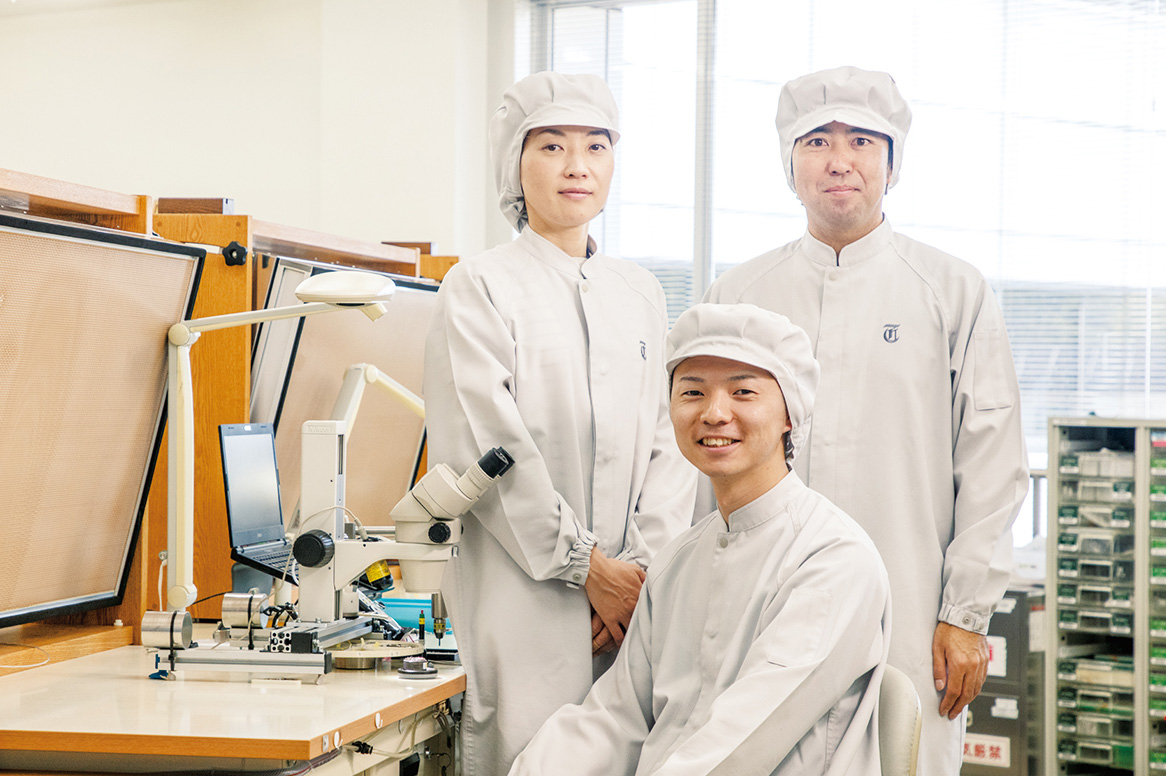

Hiroki Soma is a young craftsman in the Shinshu Watch Studio where Grand Seiko’s Spring Drive watches are made. He was awarded the gold medal at the National Skills Competition in 2015. Since manual dexterity is especially important in this work, which entails extreme precision in using tweezers to, for example, pick up and place in a watch movement a pivot that is thinner than a strand of hair, you would think that the company would select its Skills Competition entrants by testing their skills. But that was not the case. Soma says, “Out of about 200 new recruits, I was the only one who was selected to compete in the watch category of the National Skills Competition. It wasn’t that I was particularly dexterous. I don’t really remember this, but I was told that, after finishing the day’s work, I showed some ingenuity in clearing away the parts that remained.” He was selected as much for his character as his dexterity. It was his enthusiasm for his craft and the way that he applied his own ingenuity to the manufacturing process that made him stand out.

Why is ingenuity needed to assemble a watch? Aren’t patience and attentiveness to the error-free assembly of precision components enough? According to Kaori Washimi, a first-grade certified watchmaker who works at the Shinshu Watch Studio with Soma, “Every single part is made with extremely high precision, but when we assemble them we find some parts that fit less well than others.” The Spring Drive movement uses a complex mechanism called the Tri-synchro Regulator and its adjustment is central to the precision of the watch. “There are cases where we can use tweezers to adjust the part that isn’t fitting well, but since the part is related to the entire movement, we sometimes have to disassemble it completely and adjust the other parts.” This is where the ingenuity and intuition of horologists come into play.

What fosters these qualities? Washimi, who is now a leading authority on the assembly of the Spring Drive movements, says that she was strongly drawn to the innovation and beauty of this unique technology. She calls this her “love for the watch.” Of course, Washimi has great manual dexterity and technical knowledge but that is not all that it takes. “For me, the most important thing is the personal connection I feel with each watch. I love the idea that I can take these inanimate parts, assemble them and make them come alive in a complete watch.”

Shun Murayama, who was invited to work in the Shinshu Watch Studio immediately after joining the company, says, “In the beginning, even though I thought I assembled all the parts just like I was taught, there were times when the movement did not function perfectly. I often had to go around asking more experienced colleagues for a solution. This is why I like the collaborative atmosphere of our Studio and, over time, I came to understand the value of the experience that my older colleagues had gained. Watchmaking is a craft in which you never stop learning and that’s why I love it.”